Research

“Nothing in evolution makes sense except when seen in the light of phylogeny.”

- Jay Savage, evolutionary biologist

Overview

Understanding how Earth’s diversity has been shaped by evolution is one of the key objectives in biological research, and a compelling mechanism for engaging and educating the public. My research is driven by three major questions:

- What are the relationships within the arthropod Tree of Life?

- How has evolution produced such an astonishing array of form and function?

- Why are particular lineages more diverse than others?

Topics of interest to our lab group:

- Build better understanding of Araneae & Lepidoptera branches on the Tree of Life

- Train the next generation of taxonomists

- Comparative genomics of phenotypic and physiological changes

- Use of genomics as a tool in STEM outreach

Systematics

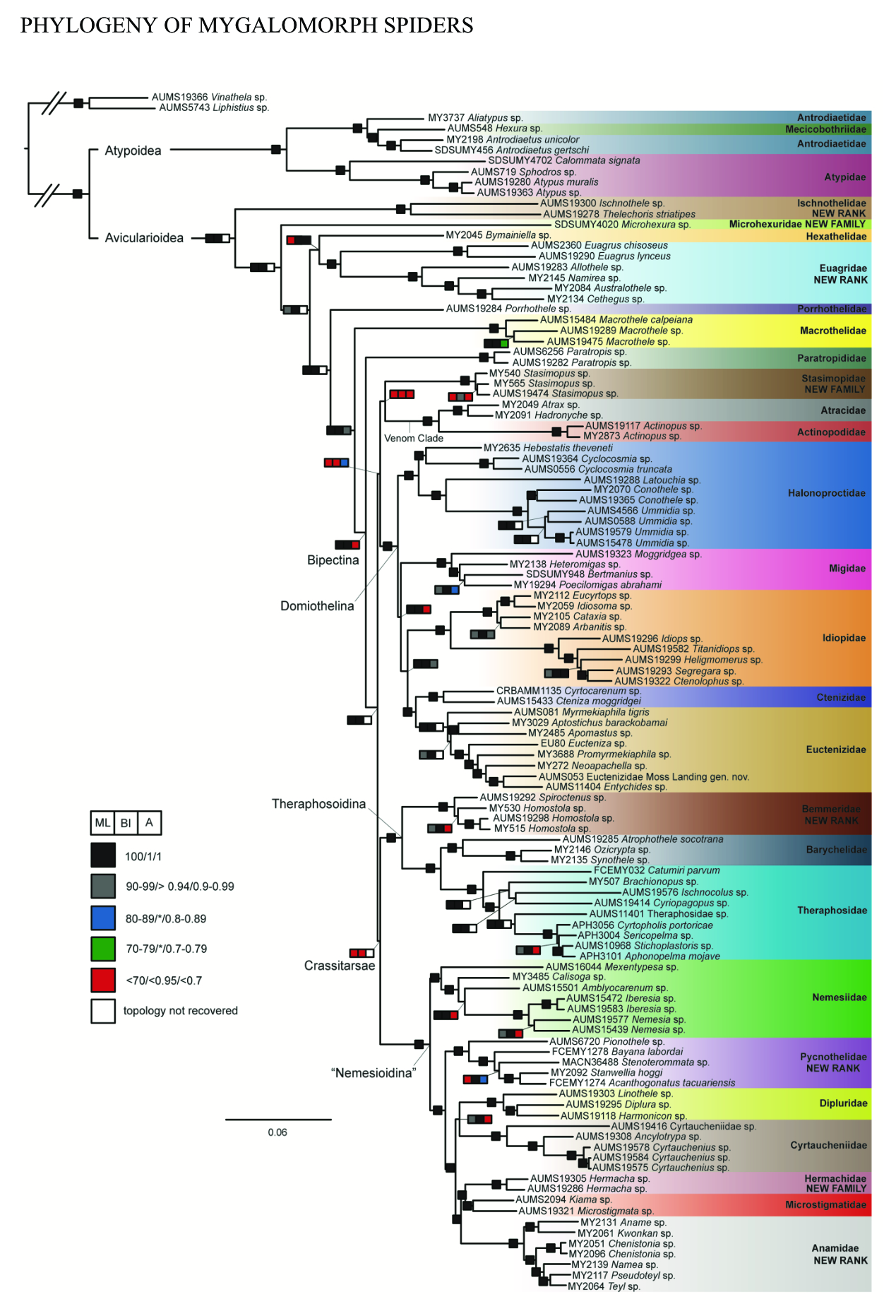

Our research addresses a wide range of evolutionary questions by investigating the history of the Araneae (from alpha and beta taxonomy to macroevolutionary dynamics to species delimitation), with a focus predominantly on the Mygalomorphae, and in particular the Theraphosidae (tarantulas). We also work on Lepidoptera, predominantly the superfamily Bombycoidea, and in particular the Saturniidae (silkmoths).

Evolution and systematics of Aphonopelma - Aphonopelma is a group where traditional morphological characters were generally ineffective at evaluating inter- and intraspecific variation, with the genus declared “one of the greatest known challenges to species delimitation in spiders”. The principal goal of this research was and is to formally resolve the species-level diversity by using an integrative approach that combined phylogenomics with morphological, geographic, and behavioral data to define species boundaries.

Understanding the Theraphosidae & Barychelidae Tree of Life - Future research will look to better understand the relationships of theraphosids and barychelids and attempt to explain how the two families are different and how they became one of the most diverse lineages of all spiders.

Evolution and systematics of the trapdoor spider genus Antrodiaetus - Antrodiaetus is a mygalomorph spider commonly referred to as folding trapdoor spiders. The genus is distributed in a classic disjunct Holarctic distribution, with Nearctic species further divided by the mountains in the East and West. This distribution is commonly found in poorly dispersing terrestrial fauna that are restricted to mesic, montane environments. Antrodiaetus species show morphological stasis and variation across their distribution. Individuals from localities separated by hundreds of kilometers may be morphologically indistinguishable, yet spiders at the same location may exhibit significant disparities in size and coloration. They represent an important focal taxon for studying the abiotic forces that influence diversity, both readily identifiable and cryptic.

Evolution and systematics of the mygalomorph spider genus Euagrus - Euagrus Ausserer, 1875 is a mygalomorph spider commonly referred to as funnel-web spiders. Euagrus comprises 20 nominal species distributed from the southern United States to Costa Rica. Since its morphological revision by Coyle (1988), the genus has received very little attention. The actual biodiversity of this group is far from known, especially in undersampled regions such as the Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands, a biodiversity hotspot consisting of 65 isolated mountain ranges (sky islands) through-out southern Arizona and New Mexico, as well as northern Sonora and Chihuahua. Under the current warming climate, the Madrean Sky Islands are expected to became increasingly isolated due to montane habitat loss, creating species and population extinctions. Therefore, documenting its biodiversity could serve as the basis for conservation management strategies in this unique habitat.

Evolution and systematics of the silk moth genus Coloradia - The genus Coloradia ranges throughout the montane coniferous forests of the western United States and Mexico. At present, there are 26 described species throughout their range, with six in the United States. These medium-sized moths are cryptically colored, with black, gray, brown, and white forewings that match the bark of pine trees. The larvae of all species feed primarily on pine (Pinus).

Body Size Evolution

Body size is one of the most important determinants of an organism’s ecological role (Hanken and Wake 1993). Because it is correlated with physiological and fitness characters, body size has been one of the most important traits evolutionary biologists have investigated. My research explores three major stories of dramatic changes in body size: 1) Miniaturization in sympatric lineages of Aphonopelma tarantulas; 2) Sexual size dimorphism in the golden orb-weaving spiders (Nephilidae); and 3) The evolution of large body sizes as an anti-bat trait in the evolutionary “arms race” between bats and moths. Future work will utilize phylogenetics, morphometrics, and comparative genomics (de novo genome sequencing and transcriptomics) to investigate the evolutionary path of these traits, as well as the putative mechanisms and the genome regions that have provided for these changes.

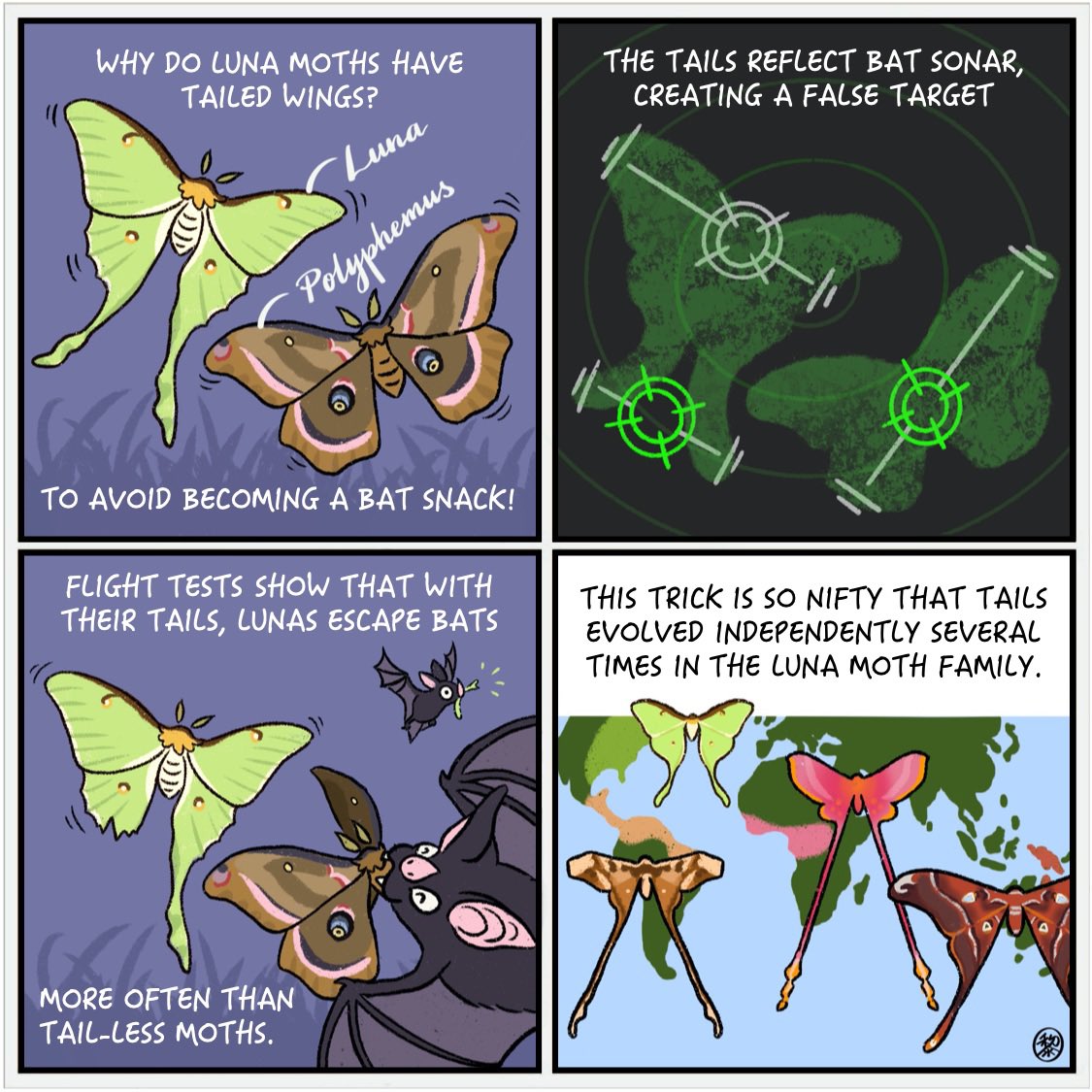

The Bat-Moth Evolutionary Arms Race

With an estimated 140,000 described species, an enormous array of wing shapes and body sizes exist across Lepidoptera. However, until recently few studies investigated the drivers of this spectacular morphological diversity. A major hypothesis I am working to answer is whether differences in moth wing shape and body size are associated with their primary nocturnal predators – bats, and if these trait differences relate to clade diversity. With their suite of anti-predator strategies (i.e., ears keen to a bat’s ultrasonic echolocation, acrobatic evasive flight, and specialized morphology to aid in defensive flight and escape mechanisms – e.g., hindwing tails and ultrasound-producing organs that “jam” bat biosonar), moths in the superfamily Bombycoidea are an ideal system to test evolutionary hypotheses concerning the historical path of anti-bat traits. Future genomic research will continue gathering the data needed to: 1) test whether there are correlated changes between anti-bat strategies and increasing/decreasing rates of speciation or extinction; and 2) decipher the functional genomics of wing shape and body size. Future behavioral work will continue growing our bat/moth behavioral interaction datasets needed to test for and quantify the selective advantage of putative anti-bat traits.

Convergent Evolution

Convergence is a striking example of the power of natural selection. But is convergence a common occurrence? Evidence is mounting that it is, yet the rules that determine the patterns of convergence we see are not well understood. It is important for us to ask why convergence occurs in some cases and not others. If we rerun the “tape of life”, will the results be the same? To do this, my research combines phylogenetics, functional genomics, geometric morphometrics, and behavioral experiments to investigate the mechanisms behind these patterns. For example, future work will look to understand whether convergence is correlated with niche and/or predatory variables (e.g., community composition, distributions, interactions), and/or genomic changes (i.e., gene expression and regulation patterns) - Can we predict where hindwing tails will evolve, or putatively have evolved, in the Saturniidae moths?

Effects of Climate Change on Pest Distribution Expansion

Adapting to changing climate is a fundamental challenge for life on Earth. Distributions change as organisms are forced to search for hospitable habitat, either retracting from areas no longer favorable or expanding into new areas with more suitable environmental conditions. Oftentimes, these changes result in taxa having a novel presence in a given area. This novelty brings with it the potential for unchecked population outbreaks due to a lack of pre-existing predators or other balancing effects that normally prevent serious environmental or economic impacts from occurring in the organism’s historical range. To gain a better evolutionary understanding of the genomic and phenotypic links of this phenomenon and its relation to climate change, we are focusing on a widespread species in the Western United States, the Pandora Pine Moth (Coloradia pandora), a species with unpredictable population outbreaks that is already expanding into novel areas, where it feeds on several pine (Pinus spp.) species, in particular the economically significant lodgepole, Jeffrey, and ponderosa pines.

Outreach

I have a very unique position here at UI. As an extension specialist, I have been tasked with building a STEM outreach and education program with the tribal students of Idaho, a role that no other faculty member at the university holds. In addition to educating K-12 tribal students in biology-centered STEM activities, I feel that my role at UI is to also be a tribal liaison in the college and my department, as well as recruiting and working to retain Native students (both undergraduate and graduate) and engaging and growing the Native community on campus.

The inclusion of underrepresented groups in biology is essential to enhancing scientific literacy in the United States and I am committed towards bringing Native ideas and representation across the campus, state, and nation. I recently created a program involving tribal students from the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma to engage them into modern biological research. This program uses the exciting bat-moth evolutionary arms race to get students into nature, collect specimens, and teaches them how to participate in DNA extraction and high-throughput sequencing with an Oxford Nanopore MinION, while also learning coding. Students take the assembled sequences, identify the CO1 barcode, and use BOLD to identify the species they have collected.

My program here in Idaho, and with the San Carlos Apache in Arizona, seeks to use genetics and the powerful evolutionary story of how it has created the vast amounts of diversity we see around us, both in humans and the rest of Earth’s biodiversity. The main focus of this new program is a genetics-based STEM outreach program to teach tribal elementary, middle, and high school students about genetics. I am currently building a genetics-based STEM outreach program to teach K-12 students about DNA, the genome, and how genes work. This program uses a LEGO DNA sequencer to teach kids about DNA, DNA sequencing, how DNA is put together to build genes, and how those genes produce phenotypes. Called Monster Lab (I did not come up with the idea, just modifying it), children use four colors of LEGO blocks to “build” stretches of DNA. These genes are then read (i.e., “sequenced”) by the sequencer (made of robotics and Arduino coding) and an output tells the students the characters that make up their monster (e.g. number of eyes, number of legs, type of monster, size, temperament, etc.). The students then get to draw and color their monster on an “official” sheet that they can hang on their classroom wall and compare with other students.

Here in Idaho, I work with the tribes to provide opportunities for the next generation to access and develop the skills and knowledge they deem necessary for strengthening Tribal sovereignty and self-determination.